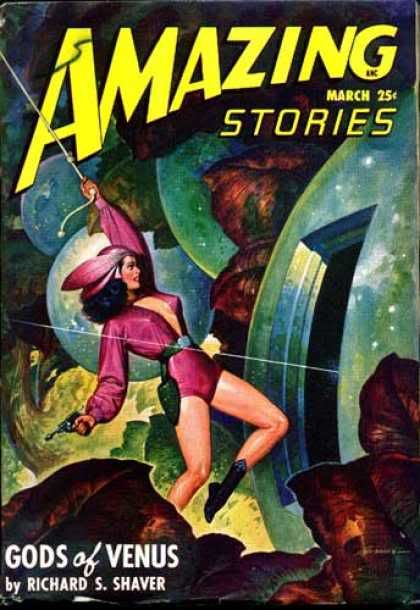

In 1943, a very strange document landed on the desk of one Ray Palmer. As the editor of sci-fi magazine Amazing Stories, Palmer was used to receiving all kinds of submissions. But this document - ominously titled "A Warning To Future Man" - was something entirely separate from the pulp mainstay.

The author, Richard Shaver, had a hell of a story to tell. He revealed - as an item of fact - that a highly-advanced species had once ruled the earth, up until a nasty burst of solar radiation some ten millenia ago drove them away. Some of these beings had apparently remained hidden in their sophisticated cavern-cities far below the surface. A few, called "Teros", were human-like and noble-natured. But the majority had devolved into sadistic, perverted dwarfs called "Deros". Shaver said "Dero" stood for 'detrimental robot' - in this sense, robot meaning emotionless and cruel.

These horrid Deros were, according to Shaver, well at work terrorising us surface-dwellers. Using the arcane technology of the ancient race - which seems to have involved all sorts of "ray" machines - they were responsible for everything from flu outbreaks to massive earthquakes. A recurrent theme, one Shaver was most obsessed with, involved the Deros abducting women for all sorts of unpleasant reasons. He described numerous such scenes with considerable relish.

The Deros also found time to zip out in spaceships, to further their nefarious goals. At this stage Ufology was not yet popular; Shaver's use of them would become significant later.

Palmer realised he was really onto something, and edited Shaver's piece for the magazine. Shaver had actually claimed this was all genuine, and that he had in fact spent eight years as a prisoner of the Deros. Palmer had to revise and re-write portions of the story to sell it as a work of science fiction - adding a plot, and removing the more graphic rape and torture scenes.

First published in AS in March, 1945, the Shaver stories saw the magazine's circulation soar. The story itself rapidly grew into a national, and international, phenomenon. Palmer would later state that AS normally got "50 to 60" letters a month; with the publication of the Shaver stories that number jumped to an incredible 50,000. Almost all of those letters were from people who claimed these stories were true - that they had experienced contact with the Deros. It grew to a point where a 1951 issue of Life magazine examined it, and the idea briefly entered into the popular consciousness.

Then came the backlash. Fans of 'hard' sci-fi were not impressed at what they called the "Shaver hoax", and ridiculed it as a publicity stunt. Astute observers noted that Shaver's claims bore all the hallmarks of paranoid schizophrenia, particularly with the elaborate, self-involved fantasy world and emphasis on an "influencing machine".

In 1948, AS stopped running Shaver's stories. Palmer would later claim some sinister coercion forced him to stop; cynics suggest declining sales and the increasing mockery of the stories were the cause. Palmer was also disillusioned when he discovered that Shaver had indeed spent eight years as a prisoner - not of the Deros, but rather as a catatonic in a psychiatric hospital.

Funnily enough, this was right around the time the UFO craze really took off. As Palmer notes in the interview below, Shaver was somewhat ahead of the curve with regard to flying saucers.

Viewed from our distant remove, it's pretty easy to be scornful of all this. Shaver was undoubtedly a disturbed guy, at time when schizophrenia was very poorly understood. The parameters of the fantasy were familiar to thousands around the world, in varying states of schizophrenic distress. It wove in a number of things - the hollow earth legend, fears of miscegenation, paranoid delusion - to create, paradoxically, a story that is utterly plausible to some.

I like to think of the Shaver stories as a great example of "found documents". This is, in essence, a work of fiction passed off as fact. They are usually first-person, and provide supporting data - maps, documents, and so on. In a sense they are something like "reality fiction" - if that makes any sense. An interesting example of the type would be Dracula. This is an epistolary novel - a bundle of documentation relating to the "Dracula case", as it were. The reader engages with Dracula more as a case study than a novel.

The genre is a particular staple in horror films - for example Cannibal Holocaust, The Blair Witch Project, and Cloverfield. The proliferation of amateur cameras and the viral power of the Internet have made this even more popular today. Back in 1997, I remember watching with bemusement a little piece called Alien Abduction: Incident in Lake County. Pre-empting the Blair Witch by a year, it was supposedly one family's amcam account of their alien abduction. The fact it ran a cast list at the end, had a wad of disclaimers, and was based on an previously revealed hoax, wasn't enough to stop many people claiming the "footage" was legit. Such is the awesome power of the media.

With regard to the Blair Witch, the producers of that little classic made a "documentary" about the case which, I thought, was even creepier than the film itself. It illustrated why I personally enjoy the "found documents" device - especially when it is well handled. A good, deep mythology is crucial to any horror story - the audience has to believe.

Another creepy trope of fiction that I fancy is the motif of harmful sensation, sometimes called the brown note. Briefly, this is like the Evil Eye, or Medusa's gaze - you look upon something and die, or at least are profoundly affected. Recently, the Ringu cycle of movies made this trope very well-known; the plot hinged on a cursed video, the viewing of which doomed the viewer.

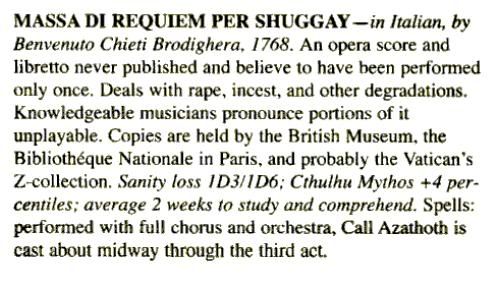

I particularly like it when the idea of the "found document" is incorporated into this motif. Not surprisingly, this combination pops up a lot in the mind-blasting horrors of Lovecraft. Only in his warped realm could one find an opera which destroys existence about halfway into the third act.

The work in question is the hideously mistitled Massa di Requiem per Shuggay. Originally appearing in one of Ramsey Campbell's brilliant Cthulhu works, the opera is passed off as a genuine document from 1769 - however it is incomplete. A grim tale is told of how the Church ordered all copies to be burnt, along with their heretical author. The score - apparently considered "unplayable" by any sane musician - isn't really the problem; it's the libretto, which is actually a veiled summoning ritual. A successful performance ends with Azathoth showing up, and he's not there to throw flowers on the stage. Here's the entry for the Massa, from the latest edition of the Call of Cthulhu RPG:

Talk about bringing down the house - there's no showstopper quite like the Daemon Sultan. It's one piece the Concert Programme won't be featuring in their Sunday Opera special, I'd wager.

No comments:

Post a Comment